The United States is embarking on a long-overdue effort to reshore parts of its manufacturing base, with policymakers pushing for economic security through domestic industry. This renewed focus on industrial policy—centered on semiconductors, shipbuilding, electric vehicles, and clean energy infrastructure—is largely framed as a response to geopolitical rivalry, supply chain vulnerabilities, and post-pandemic economic reordering.

But buried within this reindustrialization agenda is a contradiction with profound global implications: the very effort to strengthen American manufacturing could, in the long run, weaken the global dominance of the U.S. dollar. The push to reduce imports and recalibrate the trade balance may help domestic industry in the short term, but it could also undercut the very mechanisms that have kept the dollar at the center of the global financial system for decades.

The Triffin Paradox

At the heart of this tension lies the economic theory articulated in the 1960s by Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin. Triffin observed that for a national currency to function as a global reserve currency, its issuer must supply the world with enough liquidity—usually by running consistent trade deficits. However, those very deficits, if prolonged, inevitably erode faith in the currency’s value.

In modern terms, the United States has maintained dollar hegemony by being the consumer of last resort. The world exports to America, accumulates dollars, and reinvests them into U.S. assets—particularly Treasury bonds. As of Q1 2024, approximately 59% of global foreign exchange reserves were held in U.S. dollars, according to the IMF. Moreover, over $7.6 trillion of global trade is settled in dollars annually. This system has allowed the U.S. to finance its fiscal deficits cheaply and exercise significant leverage over global finance.

Yet, if the U.S. now pivots toward industrial self-sufficiency, reduces imports, and increases domestic production, it will limit the outflow of dollars that global markets depend on. The U.S. trade deficit stood at $773 billion in 2023, and a sustained effort to reduce this figure will logically lead to fewer dollars being available globally. With fewer dollars circulating globally, foreign central banks and corporations may look elsewhere—toward the euro, Chinese yuan, or other currencies—for reserves and trade settlement.

Manufacturing Revival Requires Labor—and Immigration

There is also a labor dimension to this story that policymakers must confront. To resuscitate its mid-to-low-end manufacturing sector, the United States faces a stark labor shortage. American workers, for the most part, are not lining up for repetitive, physically demanding jobs in assembly lines, textile production, or basic electronics assembly. According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, there were 8.5 million job openings in early 2024, with only 6.5 million unemployed people—leaving a gap of 2 million unfilled roles.

Unless the U.S. undergoes a complete overhaul of its education system and workforce training—which could take at least a generation—it cannot fill the needed roles with domestic labor alone. The alternative is politically fraught: accepting the presence and contributions of millions of undocumented and low-skilled immigrants who already form the backbone of many labor-intensive sectors. Roughly 5 million undocumented workers are currently part of the U.S. workforce, especially in agriculture, construction, and basic manufacturing.

Herein lies another paradox. A political movement that champions border walls and restrictive immigration laws also calls for economic nationalism and reindustrialization. These goals are misaligned unless immigration policy is reformed to recognize the labor needs of industrial revival. Without a functional immigration framework that provides legal pathways for low-skilled labor, reindustrialization will remain more aspirational than achievable.

Global Multipolarity

As American manufacturing becomes more inward-focused and the volume of global trade denominated in dollars potentially shrinks, other currencies may gain traction. China, in particular, has taken visible steps to internationalize the yuan, including through bilateral trade agreements, commodity transactions in yuan.China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), launched as an alternative to SWIFT, now processes over $18 trillion annually, signaling a growing infrastructure for yuan-based transactions.

The euro, despite its structural challenges, also remains an attractive option for central banks seeking diversification. The euro accounts for about 20% of global reserves, and initiatives by the European Central Bank (ECB) aim to further strengthen its international role. Regional currency blocs—such as those in Africa or South Asia—may gain ground as part of a broader move toward monetary sovereignty.For example, the BRICS nations are now exploring a joint payment system to bypass the dollar in intra-bloc trade, which in 2023 accounted for nearly $500 billion.

These trends suggest a gradual unwinding of the unipolar monetary world dominated by the U.S. dollar. The shift may not be abrupt, but its trajectory is already visible. The era of weaponized finance—sanctions, SWIFT access, and dollar-denominated pressure—has made many countries rethink their exposure to the dollar system.

However, policymakers must recognize that economic nationalism has global consequences. The dollar’s dominance has enabled the U.S. to run budget deficits with limited repercussions, borrow at lower rates, and maintain geopolitical clout.The U.S. national debt reached $34.6 trillion by mid-2024, with interest payments expected to surpass defense spending in 2025. If that dominance erodes, the cost of capital could rise, debt management could become more difficult, and global influence could decline.

For the rest of the world, a weakening dollar system may represent an opportunity to build a more balanced, resilient, and equitable financial order. A multipolar currency system, if managed well, could reduce systemic risk and limit the outsized influence of any single country on global finance.

Conclusion

Reindustrialization may well be a necessary correction to decades of overreliance on services and offshored production. But it is not cost-free. The very project of restoring industrial strength in America has embedded within it a tension with dollar supremacy—a tension rooted in the fundamental mechanics of global finance.

If the United States insists on a narrower, more domestically focused economy while still expecting the dollar to play a global role, it may find that the world is no longer willing to play by the same rules. In that sense, the question is not just whether America can reindustrialize, but whether it can do so without rewriting the script of global economic leadership.

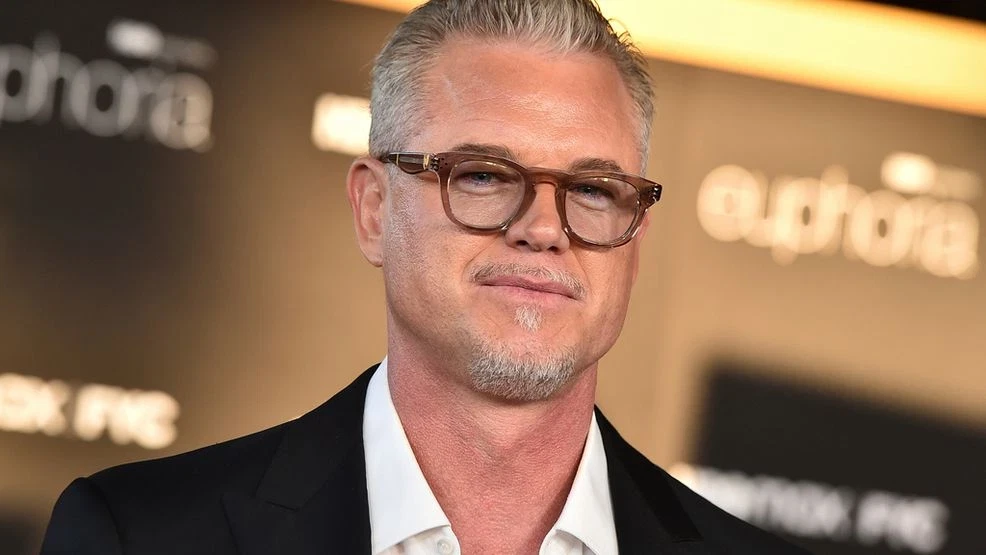

Mr. Qaiser Nawab is a global peace activist, is a distinguished international expert specializing in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Afghanistan, Central Asia and founder of the Belt and Road Initiative for Sustainable Development (BRISD), a newly established global think-tank headquartered in Islamabad, in conjunction with the one-decade celebration of BRI.

Mr. Qaiser Nawab, a global peace activist, is a distinguished international expert specializing in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Afghanistan, Central Asia and founder of the Belt and Road Initiative for Sustainable Development (BRISD), a newly established global think-tank headquartered in Islamabad, in conjunction with the one-decade celebration of BRI.