Brussels, July 23, 2025 – The Europe Today: While the linguistic battle between Dutch and French in Belgium has long dominated public discourse, a quieter, more perilous struggle has unfolded in the southern region of Wallonia. The Walloon language—once the lingua franca of southern Belgium—is now labeled “definitely endangered” by UNESCO and faces possible extinction in the 21st century.

A Romance language that evolved from Latin around the year 1000, Walloon developed alongside French, not from it, and is part of the broader langues d’oïl family that includes standard French. For centuries, Walloon thrived in the daily lives of Walloons—spoken in homes, markets, and streets. But its presence has faded drastically over the last century.

“It’s always the small who get crushed,” an old Walloon saying—”C’ èst todi lès ptits qu’ on spotche!”—poignantly sums up the fate of this marginalized language.

A Heritage Silenced by French Dominance

The decline of Walloon began in earnest following Belgium’s introduction of free and compulsory primary education in 1919, which mandated French as the sole language of instruction. Speaking Walloon—even in schoolyards—was prohibited under threat of humiliation. Teachers discouraged its use at home, resulting in generations growing up without fluent command of the language.

According to Professor Michel Francard, emeritus linguist at the Catholic University of Louvain (UCLouvain), this shift caused an irreversible rupture in intergenerational transmission.

“My grandparents were bilingual in French and Walloon,” Francard recalls. “My father was too, but my mother only had a passive understanding. I myself only became fluent during my doctoral research.”

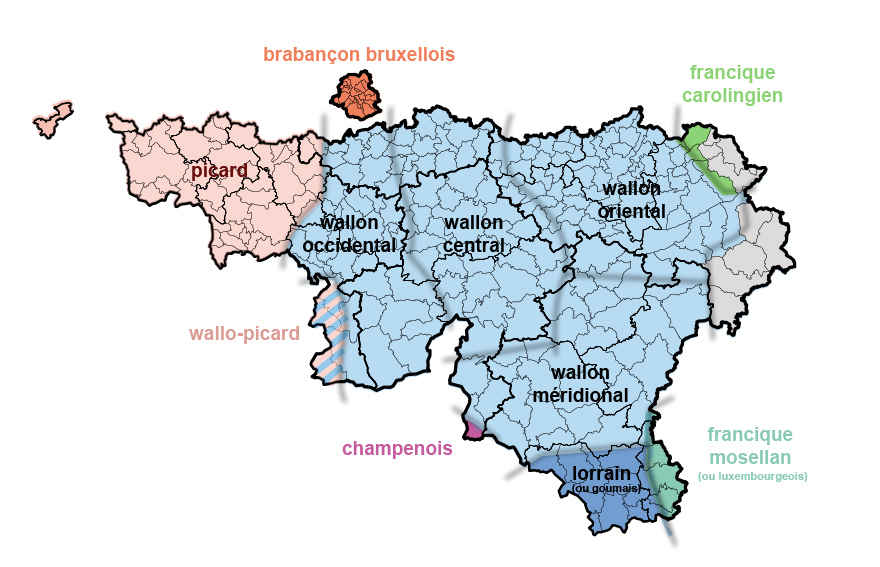

The rise of radio, television, and increased mobility after 1945 further eroded the insulation regional languages once enjoyed in rural communities. By mid-century, Walloon—alongside other regional languages such as Picard, Lorraine, Luxembourgish, and Champenois—had largely vanished from everyday speech.

Diverging Paths: Flemish vs. Walloon Movements

While Flanders engaged in a politically successful Dutchification campaign that led to language laws and institutional recognition of Dutch, the Walloon Movement did not similarly embrace regional Romance languages.

“Walloon was viewed more as a heritage to preserve than a language to use,” says Francard. “Unlike the Flemish Movement, which mobilized around Dutch, Wallonia’s energy was directed toward social and labour struggles—fought in French, the language of enlightenment and human rights.”

Walloon became synonymous with lack of education or even vulgarity, a perception that further weakened its standing. Despite its broad historical presence across Wallonia—from Namur to Bastogne—its diverse dialects were never unified or officially supported.

Today, dialects such as Wallo-Lorrain, central Walloon (Namur, Dinant), and the Picard-influenced western variant (Charleroi, Nivelles) are intelligible to scholars like Francard but increasingly alien to younger generations.

Uncounted, Unseen—but Not Forgotten

Belgium has not conducted linguistic censuses since 1947, making it difficult to assess the number of Walloon speakers today. In 1920, over 80% of Walloons reportedly spoke a regional language. Recent estimates suggest that fewer than 10% maintain even a basic level of comprehension.

Nonetheless, Walloon was formally recognized as an indigenous language of Wallonia in 1990. Symbolic gestures continue to emerge. In Liège, for instance, a new cultural trail will feature 12 engraved blue stone slabs inscribed with traditional Walloon proverbs.

Moreover, 49 communes have joined an initiative by the Brussels-Wallonia Federation to promote regional language use. Still, these measures lack the political urgency and structural support that propelled Dutch in Flanders to national prominence.

A Digital Renaissance?

There is still hope for Walloon’s revival—particularly through digital media. Francard believes that standardization, though it risks eroding regional dialects, may be essential for teaching and preserving the language.

“Thanks to the internet, resources like online dictionaries, grammar guides, and literature in Walloon are becoming more accessible,” he notes. “Contrary to initial fears, the web has not extinguished minority languages. On the contrary, it offers them unprecedented visibility.”

But time is running short.

“Intergenerational transmission is no longer working,” Francard warns. “This is typically interpreted as a point of no return unless proactive efforts are made.”

He suggests integrating Walloon as a second language in schools, promoting its use in public signage, tourism campaigns, and even branding of regional products.

A People’s Language, a People’s Choice

Ultimately, Francard is clear-eyed about the challenge: “Walloon can only be saved by Walloons themselves.”

As Belgium reflects on its complex linguistic identity, the story of Walloon is not only one of decline but also of resilience. Like the language itself, this cultural struggle quietly endures—one proverb, one speaker, one commune at a time.

Francard’s forthcoming book, 200 Walloon and Brussels Expressions to Savour—co-authored with Jean-Jacques De Gheyndt and published by De Boeck—aims to contribute to this preservation effort by celebrating the poetic richness of the language.

With political will and grassroots support, Walloon may yet find a voice in Belgium’s multilingual future—not as a relic, but as a revived thread in its cultural tapestry.