This article explores Russia’s attempt to shape a Turkic-centered framework through the “Altai as the Homeland of the Turks” narrative and the “Greater Altai” project. Moscow uses cultural diplomacy, academic forums, and cross-border initiatives to project itself as the core of Turkic civilization. The study argues that these moves are part of Russia’s broader geopolitical agenda to counterbalance the Organization of Turkic States (OTS). Altai functions as a soft-power instrument, blending culture with politics. The analysis shows that the contest between Altai and OTS is less about history and more about influence over Eurasia’s future political order.

OTS has evolved from symbolic cooperation into a regional institution. It develops shared narratives, economic projects, and cultural integration. The adoption of a common Turkic history book and a unified alphabet demonstrates institutional growth.

Russia interprets this evolution as a challenge to its influence in Central Asia. Historically, Moscow acted as the dominant power in the region. The rise of OTS threatens this position. In response, Russia promotes its own framework. The Altai narrative positions Moscow not at the margins but as a central actor in the Turkic world. This paper analyzes how the Altai narrative operates. It examines the instruments used, the competition with OTS, and the long-term implications for Eurasian geopolitics.

Altai as Strategic Narrative

The Altai region is framed as the birthplace of Turkic languages and early states. Russian historians stress Altai as both sacred and inclusive. It is presented as a space of coexistence between Turkic and Slavic peoples. This narrative legitimizes Russia’s claim to be a guardian of Turkic heritage.

Altai becomes a cultural symbol with geopolitical utility. By anchoring Turkic history inside Russian territory, Moscow strengthens its role as a civilizational center.

Instruments of the Altai Framework

Russia uses several instruments to institutionalize this narrative:

- Academic initiatives: International Altaic Forum in Barnaul creates a scholarly platform for legitimization.

- Publications: The Chronicle of Turkic Civilization provides an alternative history.

- Youth engagement: State-backed Turkology programs train a new generation of researchers.

- Cross-border projects: The Greater Altai initiative links Russia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and China under ecological, scientific, and cultural cooperation.

While these initiatives appear cultural, they are politically driven. They seek to integrate Turkic heritage into a wider Eurasian identity aligned with Russian interests.

Political Use of Cultural Narratives

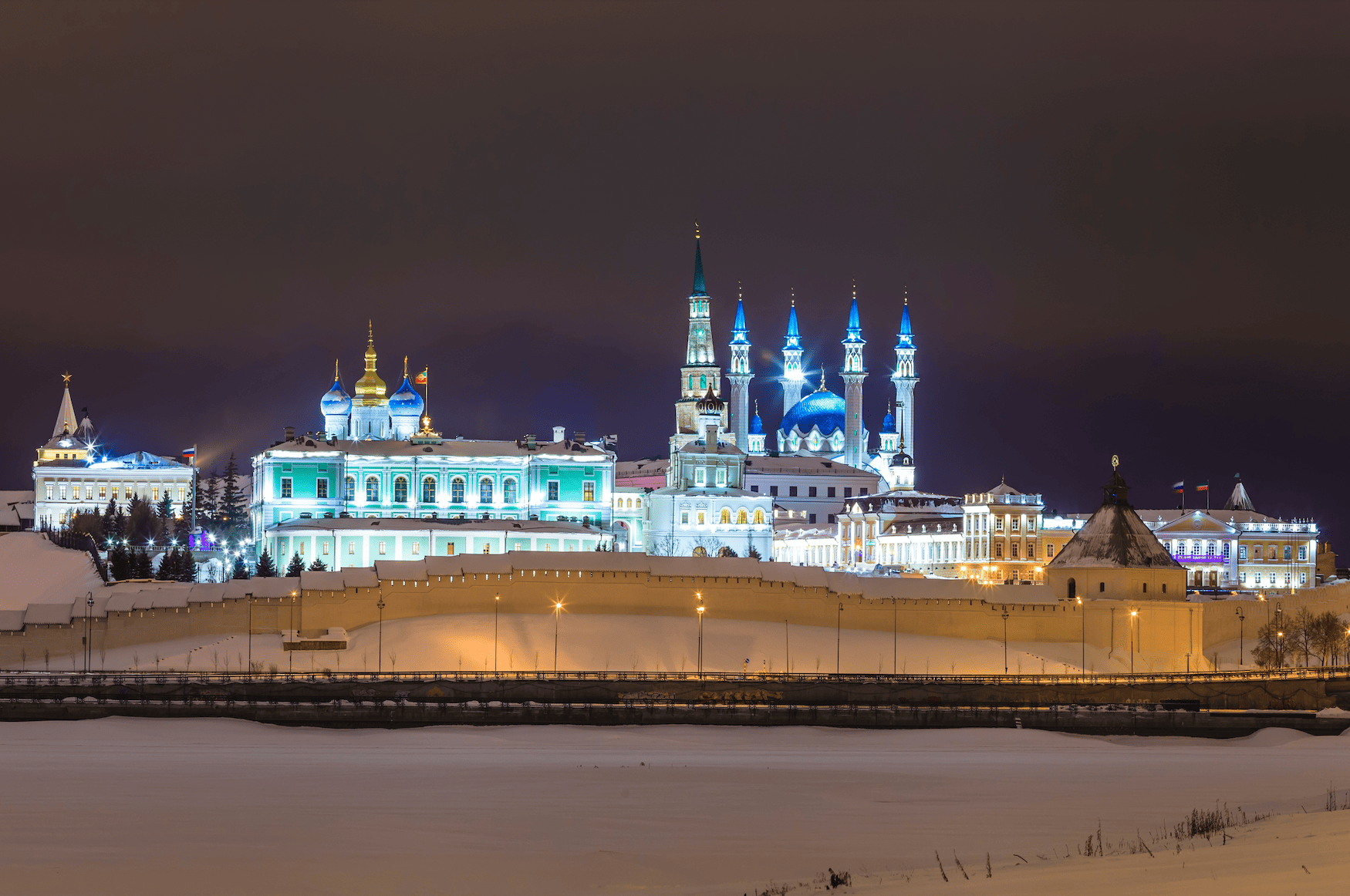

In July 2025, Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin hosted leaders from Kazakhstan, Armenia, Belarus, and others at Manzherok in the Altai Republic. Officially, the forum focused on ecology. In reality, it served as a stage for discussions on trade, integration, and Eurasian cooperation.

This case illustrates how cultural platforms become political projects. Altai operates not as neutral heritage but as a tool of influence.

Competition with the OTS

Central Asian states balance carefully between Altai and OTS:

- Kazakhstan: Recognizes Altai as the “sacred cradle” but remains deeply invested in OTS initiatives such as the history book and alphabet.

- Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan: Participate in Altai festivals and expeditions, but avoid deeper commitments.

- Türkiye and Azerbaijan: Focus on strengthening OTS, while keeping Altai at a distance.

OTS continues to move forward. The Turkic Academy coordinates the common history book. The unified alphabet, approved in 2024, is gradually being implemented. Russia views both developments with suspicion.

Implications for Eurasian Geopolitics

The Altai framework is more than cultural heritage. It is a geopolitical tool with several implications:

- Challenging OTS legitimacy: Altai projects reduce OTS’s claim to be the sole institutional representative of Turkic unity.

- Eurasian identity over Turkic identity: Russia redefines Turkic heritage as part of a broader Eurasian civilization.

- Dual strategies by Central Asia: States may adopt both frameworks, reducing the coherence of OTS.

- Expansion of Russian soft power: Academic and cultural initiatives strengthen Moscow’s influence among younger elites.

- Future rivalry: The competition may extend to education, cultural policy, and regional security.

Conclusion

Russia’s Altai narrative is a strategic project. It blends history, culture, and politics to counterbalance the Organization of Turkic States. Unlike open confrontation, Moscow uses cultural diplomacy and soft power. By embedding Altai into Eurasian institutions such as the SCO and EAEU, Russia ensures that Turkic identity is not independent but linked to Moscow’s vision of Eurasia.

The outcome depends on two variables: the institutional strength of OTS and the balancing strategies of Central Asian states. If OTS consolidates its cultural and political initiatives, the Altai project may remain symbolic. If OTS faces fragmentation, Russia’s Altai framework may become an influential alternative.

In essence, the Altai narrative is a geopolitical instrument disguised as cultural revival. It signals Russia’s determination to remain central in the Turkic world, not as an outsider but as a claimed historical homeland. The competition between OTS and Altai will shape the future of Eurasian identity and regional order.