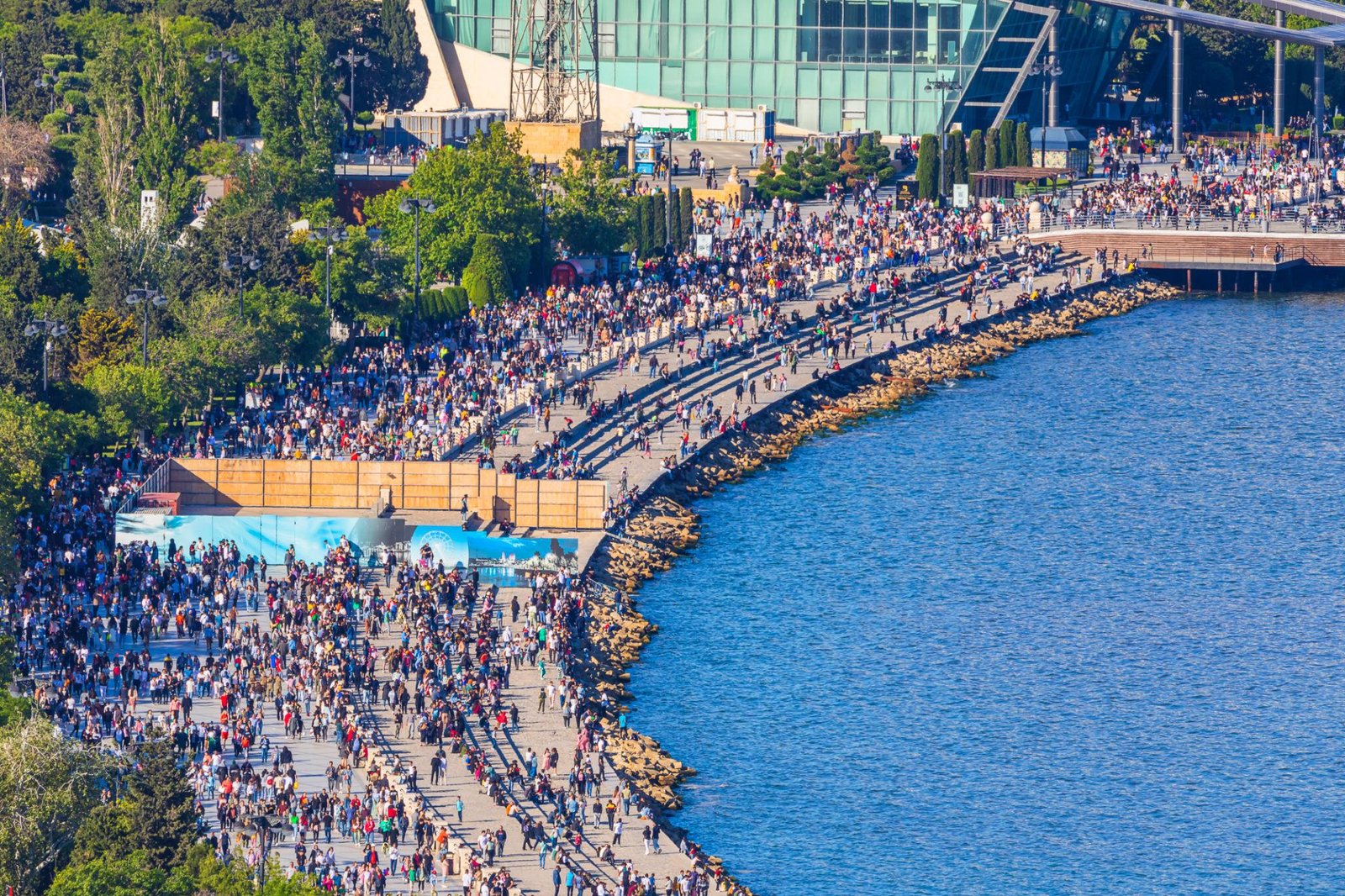

As the global community convenes in Baku for COP29, the precarious reality of nearly one billion people living in urban slums demands urgent attention. These marginalized communities, emblematic of deep-seated socio-economic inequalities, bear the brunt of climate change’s harshest impacts. Yet, their struggles remain peripheral to mainstream climate discourse. While COP29 seeks solutions to the climate crisis, it must address the systemic inequities at the intersection of climate change and public health challenges in slums—inequities perpetuated and exacerbated by the mechanisms of capitalism.

Slums are a direct byproduct of industrialization and urbanization, both driven by the imperatives of capitalist development. The Industrial Revolution uprooted rural populations, forcing them into cities where they formed a burgeoning working class. Deprived of adequate infrastructure, these urban spaces became breeding grounds for disease, as Edwin Chadwick’s 1842 report highlighted. The subsequent Public Health Act of 1848 and Joseph Bazalgette’s transformative sanitation projects in London addressed immediate health crises but primarily served to sustain a productive labor force. This utilitarian approach—ameliorating symptoms while preserving the exploitative structure—remains a hallmark of responses to slum conditions today. Fast forward to the present, urban slums in global metropolises reveal the crisis of “urban informality” on a staggering scale. According to UN-Habitat, nearly a quarter of the global urban population lives in slums, lacking access to essential services. David Harvey’s critique of urbanization illuminates the structural inequalities inherent in capital accumulation, which shapes cities to prioritize wealth generation for elites over equitable development. Mike Davis’s “Planet of Slums” starkly portrays how neoliberalism has expanded slums, creating “surplus populations” that are simultaneously exploited and excluded from mainstream economic and social systems.

These vulnerable populations bear a disproportionate burden of climate change. Rising temperatures, erratic weather patterns, and flooding compound their already precarious existence. During fieldwork in the slums of Islamabad and Rawalpindi, I encountered daily wage laborers and domestic workers whose lives were disrupted by heatwaves and water shortages. These individuals, whose carbon footprints are negligible, suffer the most from global carbon emissions. Overcrowded conditions, poor drainage, and lack of resources create breeding grounds for vector-borne diseases such as dengue and malaria, exacerbating public health crises. According to the WHO, climate-sensitive diseases disproportionately affect populations in informal settlements, with slum dwellers twice as likely to contract diseases like cholera during floods compared to those in formal urban areas. COP29 discussions have, unfortunately, often skirted the root causes of these crises. As Joseph Stieglitz argues, neoliberal capitalism, with its relentless focus on profit, entrenches inequality, rendering vulnerable populations expendable. This systemic exploitation underscores a triad of oppressions in slums—health, education, and economic marginalization. Limited access to healthcare leads to preventable diseases becoming endemic; for example, maternal mortality rates in urban slums are double those in rural areas in many developing countries. Education remains out of reach for many, with children compelled to work instead of attending school. Economically, these communities are ensnared in cycles of debt and precarity, with climate shocks further exacerbating their plight.

Frantz Fanon’s “The Wretched of the Earth” offers a lens to understand slum dwellers as a modern subaltern class, oppressed by global hegemonic structures that render their struggles invisible. Dialectical materialism reveals how capitalism sustains itself by creating and maintaining marginalized spaces as reservoirs of cheap labor while denying their inhabitants dignity and opportunity. Historical parallels with industrial London underscore the continuity of these dynamics. Jackson Lee’s “Dirty Old London” chronicles how unchecked industrial capitalism created unsanitary, disease-ridden environments. While public health reforms alleviated suffering, their primary aim was to ensure workforce productivity—a pattern that persists in contemporary slum interventions, which often fail to address systemic inequities. The commodification of healthcare under capitalism further entrenches these disparities. In “Slum Health: From the Cell to the Street”, Jason Corburn and Lee Riley emphasize the urgency of dismantling systemic barriers to health equity. Women in slums, for instance, face disproportionate challenges, including limited access to reproductive healthcare and exploitation in informal economies. The crisis of national health systems worldwide—exacerbated by privatization—underscores capitalism’s inability to prioritize public welfare over profit. In India alone, nearly 70% of urban slum dwellers rely on unregulated private healthcare providers, often falling into debt for basic medical care.

Slums are not merely sites of poverty but political spaces shaped by historical and contemporary power dynamics. Neoliberal policies of privatization and deregulation have exacerbated inequalities, creating a stark center-periphery divide. Postcolonial critiques reveal slums as enduring legacies of colonial exploitation, while postmodern perspectives expose the neocolonial structures that sustain these inequalities. While subaltern studies highlight the agency and resilience of slum dwellers, their survival strategies alone cannot dismantle the systemic forces driving climate change and inequality.

The political economy of slums underscores how global capitalism extracts labor and resources from these peripheral spaces to enrich urban elites. Mike Davis’s concept of surplus populations reveals the structural injustices that render slum dwellers disposable in neoliberal economies. This extraction perpetuates a cycle of poverty, health crises, and climate vulnerability that COP29 must confront head-on. Justice and equity must be integrated into its climate agenda, ensuring that those most affected by climate change are not excluded from solutions. Solutions require a transformative approach. Paulo Freire’s framework of emancipatory education offers a path forward by empowering slum populations with critical consciousness to challenge their oppression. Health, education, and environmental sustainability must be interconnected priorities. A redistributive economic system, informed by Marxist principles, can challenge capitalism’s stranglehold. Wealth redistribution, public infrastructure investment, and the dismantling of monopolistic practices are crucial steps. The spirit of Awami Quwat—the power of the people—must guide these transformative efforts, fostering unity and collective action.

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 3 on health and wellbeing, is impossible without addressing the systemic inequities faced by slum populations. Climate change, as a product of capitalism, threatens not only the environment but the very fabric of human society. COP29 discussions must move beyond technocratic solutions to confront the root causes of these crises, embedding equity and justice at the heart of climate policy. Having witnessed the resilience and suffering of slum dwellers firsthand, I advocate for policies that center their voices and needs. The path to sustainable development lies in dismantling oppressive structures, fostering global solidarity, and committing to justice for all. Only then can we envision a future where health, dignity, and sustainability are universal rights—not privileges. The outcomes of COP29 must reflect this commitment, setting a precedent for a world that values people over profit.

Prof. Dr. Muhammad Shakeel Ahmad is Chief Executive of Global Strategic Institute for Sustainable Development (GSISD).